Lawer Ibrahim El-Hilbawi, The Executioner of Denshawai !

The Denshawai incident occurred in 1906, and El-Hilbawi, despite his efforts and the defense from his friends who used all their tools to defend him, was never absolved by history, even though they failed to convince the public of his innocence. I see a similar situation unfolding with some of the prominent lawyers of modern times in Egypt’s courts under President Sisi, in the absence of justice within the current Egyptian judicial system.

There is a stark contrast between the events of Denshawai and those of today, yet the victims of history are much the same.

What is the story of Denshawai?

The Denshawai incident refers to an event that took place on June 13, 1906, in the Egyptian village of Denshawai, located in the Monufia Governorate, to the west of the Nile Delta. The incident escalated between five British officers and Egyptian farmers, resulting in the deaths of several Egyptians, including a woman, and the death of a British officer from heatstroke. The most significant aspect of the case — and what made it historically memorable — was the brutal response of the British authorities, who had been occupying Egypt for a quarter of a century at the time, led by Lord Cromer, and the arrogant, harsh way the sentences were carried out.

The case left a lasting impact, and Ibrahim El-Hilbawi, the first head of the Egyptian Bar Association, paid a heavy price, despite having been elected six years after the incident. Today, we will read El-Hilbawi’s defense of himself, as he recounts the details of this case from his personal memoirs.

El-Hilbawi’s Account:

The Denshawai case, which I never believed I alone deserved the bad fame it left, as there were many others who were more deserving of this dishonor. This incident occurred on Wednesday, June 13, 1906, and I was traveling from Cairo to my estate near Sidi Ghazi (in the Beheira Governorate) several hours before the incident occurred. I remained there for the rest of that day and the next two days (Thursday and Friday).

The reason for my trip was a dispute between me and Ahmed Khairy Pasha, the director of the General Waqf Department. The dispute was due to an old mound in the middle of his land, which the Real Estate Authority had authorized him to purchase to use for fertilizing his land. My brother, who was managing my land affairs, advised me to claim the mound for myself, as it was a public benefit that we had the right to take earth from it. I complained about the permit issued by the Real Estate Authority, and Khairy Pasha responded that his land had other mounds, and I did not need the one in the middle of his land. I learned that the Real Estate Authority’s representative would visit on Thursday or Friday to review this issue.

At 9 a.m. on Friday, June 15, Mr. Anthony, the director of the Real Estate Authority, and the late Mohamed Basha Abaza, the inspector, visited me at my home before going to inspect the mounds. During our conversation, Mr. Anthony mentioned the Denshawai incident, which had occurred on Wednesday, but I had not yet heard of it, as the Thursday newspapers, which carried the news, only reached me by 10 a.m. the next day. I was deeply saddened by the news.

Later, I continued my trip to Cairo, and upon arrival, I found a messenger from Mustafa Fahmy Pasha, the then prime minister, requesting my presence at the Ministry of the Interior. They wished to appoint me as the Deputy Public Prosecutor for the case that was about to be brought before the special court for trial, on behalf of the government, against the Denshawai villagers. They chose me because I was the senior and most experienced of the lawyers available. I remembered that, for the first case under the special court law, the government had chosen the late Ahmed El-Husseini Basha, the oldest and most senior lawyer, to represent the prosecution. I found no reason to refuse the assignment. I requested my fees, which were set at 300 pounds, and I specified that my role would be limited to representing the prosecution before the court without being involved in the investigation.

The investigation was conducted in Monufia by Public Prosecutor Mohamed Ibrahim Basha and Mohamed Shoukry Basha, the Monufia Governor. The case file reached Mansfield Pasha, who, with Mr. Mugherly, the Interior Ministry Inspector, reviewed the investigation papers without my involvement. They prepared the indictment, referring 51 defendants to the special court, with a request for the death penalty for all.

When the case came to me, I noticed that there was a grave injustice in not distinguishing between the defendants’ responsibilities. I requested to exclude 15 defendants from the death penalty, explicitly requesting this during the session. After a discussion, I succeeded in convincing them to accept my request.

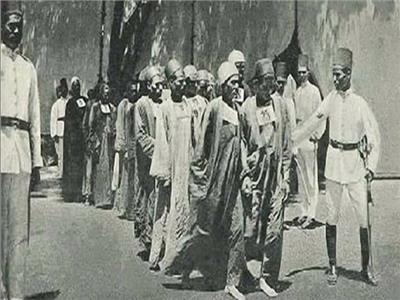

The trial session was held in a large tent capable of holding around 3,000 people. The witnesses included prominent figures from the Monufia governorate and surrounding areas. The trial panel consisted of the late Boutros Pasha Ghali, the chief judge; late Fathy Pasha Zaghloul; and the British judge Mr. Bond, the head of the Appeal Court, along with other officials.

During the session, I passionately presented my defense, without stepping beyond what was required. In fact, I can admit that my national pride even led me to feel more than what my duty demanded, as I had invited the defense lawyers for the accused to my office in Shebin El-Kom the day before the trial to brief them on the arguments I would use in my defense.

I spoke for over three hours in the trial, and the public did not show any disgust or criticism of what I had said. After the session was adjourned, I was greeted warmly by most of those present for the defense I provided.

The defense of the accused did not take more than an hour and a quarter. After the harsh sentence was delivered — the execution of four by hanging and six being publicly flogged in front of their homes — there was a sense of terror and shock. I was perhaps the most affected by the horror of that moment. When I was asked by Boutros Pasha Ghali, the head judge, for my opinion on the verdict, I compared myself to a mother who had been told by doctors that her child could only be saved by amputation. She agrees, but upon hearing the news, she wails in sorrow.

The verdict, delivered by a court that represented the British interests, sentenced four to death, and the rest to flogging. And thus, the campaign of public condemnation and accusations of treason against El-Hilbawi began in the newspapers, where he was dubbed "The Executioner of Denshawai." On the other hand, the Egyptian judges who had unanimously sentenced the accused to death were not subjected to similar scorn.

El-Hilbawi, the first head of the Bar Association since its founding in 1912, was forever remembered for his role in defending the British against Egyptians. His actions have been permanently etched in history as a shameful mark on his legacy. Similarly, defending a judge who insulted a fellow lawyer before the court might tarnish the careers of some prominent lawyers forever.